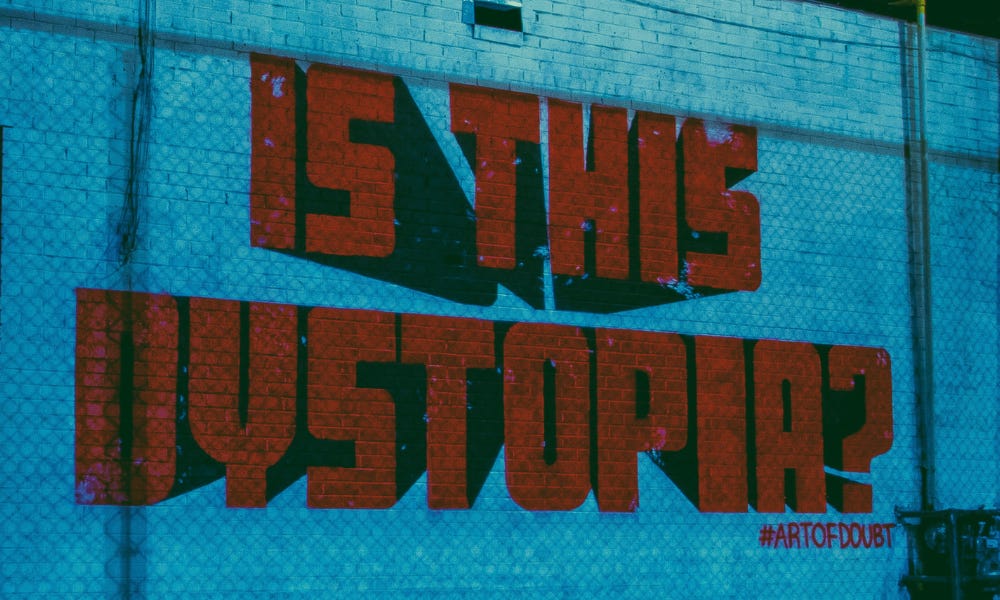

Your utopia is my dystopia: Bitcoin, CBDCs and two visions of the future

Utopian visions of ‘the best world possible’ are always dystopian. Some thoughts on visions of the future, George Orwells 1984 and how Bitcoin and CBDCs fit into this.

When I read Brave New World and 1984 at school, I found both dystopias shocking - and hard to believe. Who would want to live like that? Why would anyone accept this? This was towards the end of the 1990s when, for political scientist Francis Fukuyama, the end of history seemed to have finally arrived. Communism was defeated, and optimism was the order of the day. Clinton, Blair, and Schröder had taken the helm as eloquent, dynamic feel-good progressives. Democracy had triumphed, the internet was seen as a force for good that would make the world freer, smarter, and, above all, more democratic.

This stability manifested itself pop-culturally as crushing boredom. In 1999, a series of Hollywood films were released that were all dedicated to this theme. The Matrix, Fight Club, as well as the cult classic Office Spaces (immortalized in thousands of quality memes), made 1999 the year of the "cubicle movies": films in which the protagonists steadily lose their minds in boring, unfulfilling, dull jobs - and take on the hero’s journey by finally managing to break out of a grueling illusory world. They do this by showing not only their bosses but also society as a whole the middle finger.

The fact that the cubicle, the cell-like individual office in which Keanu Reeves hid from the agents of the Matrix, was replaced by the open-plan office in the years that followed is an interesting allegory for society as a whole. 20 years after 9/11; with the rise of (right-wing) populist parties and sleazy political figures worldwide; an increasingly fragile financial system and social media and politicians harnessing their unfiltered efficacy, it seems to be emerging that privacy and freedom may not be the highest good after all. And that history is back with a bang.

Your utopia is my dystopia

Today, we find ourselves in the midst of the corona pandemic, climate change that has now been upgraded to a catastrophe, and a campaign of bloody conquest emanating from Russia that is making waves far beyond Europe in terms of food and energy. There is less and less room for nuance and factual debate in the face of monumental threats that feel ever more acute day by day.

In this environment, two fundamentally different concepts of society are emerging. The crushing boredom of the late 1990s has given way to a mood that is most reminiscent of sitting in a pressure cooker: The imminent end of the world is conjured up on both the left and the right and is repeated on Twitter, YouTube, Netflix and good old linear TV every single day. The only way out seems to lie in Utopia.

“A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.” - Oscar Wilde

A few weeks ago I read the excellent 'The Ministry of Truth' by Dorian Lynskey and I can’t recommend it enough. Broadly speaking, it is about the genesis of George Orwell's novel 1984, which is popular as ever these days. At least as a cross-reference, because anyone who has read (and understood) it knows that Orwell's book is more of a surrender than an indictment. Orwell, as a leftist, was disillusioned with the atrocities and authoritarian crimes of Stalinist socialism, which survived the now defeated fascism that had been deemed a failure. Orwell wrote 1984 in the years 1946 to 1948 and was convinced that in the struggle against Stalinism, democracies like England would sooner or later also drift in an autocratic direction. But above all, the purposelessly oppressive world of ‘Airstrip One’, as England is called in 1984, was the ultimate reckoning with the naïve utopias of his time.

A Utopia is as simple as it is naïve: people live happily in a perfect world. There is no suffering, no poverty, no diseases. But if you think a little further and look behind the scenes, you often find an ugly grimace hidden in these worlds. 1984 is the ultimate satire on (socialist) Utopias. It puts an intelligent, sane, critical-thinker in a stupid, crazy, indoctrinated world.

Orwell described totalitarianism in 1941 as follows :

“The peculiarity of the totalitarian state is that though it controls thought, it does not fix it. It sets up unquestionable dogmas, and it alters them from day to day. It needs the dogmas, because it needs absolute obedience from its subjects, but cannot avoid the changes, which are dictated by the needs of power politics. It declares itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.”

Bitcoin and CBDCs

Two utopias (or dystopias, depending on your point of view) with the greatest radiance of our time find their ideological focal point in Bitcoin and CBDCS: self-determination versus the collective; decentralization versus central planning; privacy versus surveillance. Bitcoin's ideological roots go back to radical laissez-faire libertarianism, in which the state is supposed to play a minimal or even no role in people's lives. In this world, central banks, which hold the monopoly on money, are seen as power-hungry, corrupt, elitist bureaucrats. The Austrian School after Mises or Hayek denounced this model as over-bureaucratization, which put the state and not people at the center and would ultimately undermine the mechanisms of the free market and thus human trade.

Bretton Woods, the hegemonic role of the US dollar, the (supposedly temporary) abolition of the gold standard in 1971 by Nixon, and the bailout of banks by the state in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis (which was the emblematic launch pad for Bitcoin) are considered evidence of this abuse of power. The solution? Digital gold is also capable of acting as a payment network like PayPal. A system that is designed from the outset to be anti-fragile, that cannot be hijacked by a charismatic leader, and whose trust is secured at its core through a kind of cooperative competition. Bitcoin's most important aspects are often counterintuitive and full of paradoxes: it needs cooperation and community to develop the open-source project. At the same time, it empowers the individual and praises egoism and self-empowerment as the core of human nature that stabilizes our coexistence as a society.

On the other hand, you have a new strain of progressive politics that also wants to ‘fix’ the global financial system, which is kept on life-support since 2008. But the medicine of choice is the direct opposite: Instead of taking central banks out of monetary policy, it wants to give them more power than ever. I’ve written about CBDCs already, so I’m gonna shamelessly cite myself:

CBDCs are in every regard the polar opposite of Bitcoin. CBDCs mean total centralisation; mighty central banks; easy to implement monetary policy changes; complete control of the population by, e.g. adding a date of expiry to money to stimulate consumption (the ECB is openly talking about this in their paper) and the ability not just to ban people from access to bank accounts, but completely turning money off like a light switch.

Of course, CBDCs are officially presented as something that needs to be done and as something good. As always, there is no evil plot. But power like that can be abused and democracies can turn into dictatorships.

It’s important to note that leftist thinkers and edgy Modern Monetary Theory economists love the idea of CBDCs. It’s the perfect tool for more control, for more central planning. Here’s what Yanis Varoufakis has to say about it:

That last move, the digital yuan, constitutes a revolution: when fully-fledged, it will equip every resident in China, but also anyone from around the world who wants to trade with China, with a digital wallet – a basic digital bank account. In one move, therefore, the commercial banks will have been ‘dis-intermediated’; or, in plain English, they will have lost their monopoly over the payments system. This is genuinely a radical break from finance as we have known it. And, yes, it is one that we should emulate in Europe and in the United States – which is, of course, why Wall Street and the rest of the West’s financiers will do their best to stop it, preferring to blow up the world rather than allow themselves to be… dis-intermediated.

Techno-feudalism versus the almighty state

Both Utopias are on shaky grounds. The concentration of power is never good. In the hands of a few tech companies and founders suggests that we are heading for the world of Neil Stephenson's Snow Crash. In it, corporations have taken over the territorial monopoly of power from states, the richest of the rich are building their own floating paradise (hello Peter Thiel) and the broad masses are escaping their dreary, misery-ridden daily lives into the colorful metaverse (the ubiquitous buzzword Stephenson invented in his book that vacillates between shocking dystopia and action-packed boy's dream).

Opposed to this are states, political parties, and societies increasingly inclined towards authoritarianism. The individual freedom held dear in Bitcoin is being replaced here by a society oriented towards the common good. The successful European model of social democracy and social market economy (to which I myself am not averse) does not go far enough for many in the fight against inequality, climate change, and the alarming concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Instead of less government, as the winners of the internet age and automation demand, there should be much more government. The Transparent Man, which was a dystopia in the 1990s, is now a reality. Tech companies are fleecing our data and willingly handing it over to the best bidders or feeding the gluttonous mouths of governments around the globe.

Privacy and personal responsibility as adversaries

The extreme form that makes George Orwell's 1984 dystopian world seem almost amateurish is the totalitarian, digitally-automated China of the 2020s. The proles, the workers who make up about 85% of the population in Orwell's Oceania, are deliberately kept stupid and powerless, but are otherwise ignored by the one-party state and are consequently less paranoid and psychologically burdened. Big Brother and his thought police focus largely on the inner and outer party members, whose total loyalty is monitored and questioned on a continuous basis.

It is different in totalitarian China, where total obedience has been automated. It could be scaled easily, as they like to say in the tech industry. The central element here is the social credit system. A points system that is reminiscent of a video game, in which desirable behavior is rewarded and undesirable behavior is punished. In China, undesirable behavior is not only ignoring a red traffic light but also criticizing the communist party.

But not only China, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the NSA, and other intelligence agencies all leverage technology to watch their citizens closer than ever. As Lynskey writes:

“Oceania’s surveillance apparatus was nothing compared to what we have available today. (…) The internet was a development that promises social control on a scalte those quaint old twentieth-century tyrants with their goofy mustaches could only dream about.”

The operating principle of panopticism is the knowledge of the constant possibility of a supervised person being observed by his supervisors: "The person who is subject to visibility and knows this takes over the coercive means of power and plays them out against himself; he internalizes the power relationship in which he plays both roles at the same time; he becomes the principle of his own subjection."

Over a longer period of time, this mechanism leads to an internalization of the expected norms, and thus from cost-intensive external coercion from the point of view of the norm setter to a cost-effective self-coercion (self-disciplining). It "gives power to the mind over the mind" and is a method of gaining power "on an unprecedented scale", "a great and new instrument of government".

Utopia and reality (fortunately) diverge

Utopias and dystopias are not bad per se. They can serve as a guide for political movements, a kind of North Star so that one knows roughly what one is fighting for (or against) and where the journey is likely to go. Fortunately, the soup is usually not eaten as hot as it is cooked.

“Utopias appear much more realizable than we had formerly supposed. And now we find ourselves faced with a question which is painful in quite a new way: How can we avoid their final realization.” - Nicolas Berdiaeff

Just as no one who sees Bitcoin as a meaningful innovation calls for anarchism and the complete abolition of the state, representatives of CBDCs do not see the Chinese techno-dictatorship as a desirable model. After all, there are nuances and in-betweens. And above all, there are different views and political debates about where things should ultimately go.

Just as George Orwell was wrong in his prediction that the democratic West would itself become one in the fight against authoritarian dictatorships, I also think today's doomsday scenarios are exaggerated.

However, I’d like to close with some sentences from the ending of Lynskey’s The Ministry of Truth:

“Liberal values are not indestructible, and they have to be kept alive partly by concious effort. (…) The moral to be drawn from this dangerous nightmare situation is a simple one: Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.”

Like what you read? Send this newsletter to a friend, subscribe (if you haven’t yet) and follow me on Twitter.

Photo by Alex Kristanas on Unsplash.