Stagflation is here - now what?

Europe seems to enter a stagflation period, last seen in the 1970ies. What it means and how it will affect us.

Europe has definitely seen better days. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine still ongoing, we’re witnessing the most dangerous geopolitical crisis since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. On top of that, we’re seeing multiple additional ongoing and emerging crises.

We’re heading into uncertain Winter months. Our dear experts are now pretty much confident that inflation and blown-up central bank balance sheets actually won’t “come down in due time” and that it doesn’t look to be “transitory”.

The World Bank and a lot of other official bodies are not trying to keep their cards close to their chest, but are issuing warnings that Europe is heading into Stagflation.

So now is probably a good time to take a closer look at what Stagflation is, what it means for people living in such economies, and what we can learn from the 1970ies.

What is Stagflation?

I described it in a previous post as follows:

Stagflation with high-interest rates and a shrinking economy is what follows. Meaning prices of stuff continue to rise, while you have a lot of unemployed people. No one wants that, especially not short-term-gain politicians. Extreme political positions become more popular, which will end in suffering for all of us as history has taught us. We don’t want that.

Sometimes stagflation is also called recession-inflation, which is exactly what it is: A shrinking economy combined with high or even rising (price) inflation.

The term stagflation was invented and often used during the 1970ies when we faced a similar energy crisis. Up until then, most economists believed that there is an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. So unemployment was supposed to fall when inflation rises because the higher prices would encourage businesses to produce more and hire more people. The other way around, they thought that during a recession and higher unemployment, inflation would come down automatically as demand decreases.

The 1970ies showed that in fact, both are possible at the same time: a shrinking economy, plus rising prices.

What Stagflation means for us

Two bad things at once: A higher chance for unemployment or less demand for your services as companies tend to reduce their headcount or costs in general. At the same time, the prices of goods and services, you (or your business) need are continuing to rise.

In our case, one of the main drivers for rising costs is not an overheating economy due to super low-interest rates. But supply-side shortages of hard commodities gas, fuel, fertilizers, grain, and other crucial things that the economy needs to run properly.

Meanwhile, governments and central banks are trapped between a rock and a hard place as they will (understandably) try to save people and businesses from going bankrupt. They try that by coming up with all kinds of mechanisms that are supposed to lower prices. And on the other hand side, they have to increase interest rates to fight inflation.

Both measurements are working against each other, I like to picture it as a boat that is nearly capsizing, and you’re trying somehow keep the balance. Making it worse in the process.

What we can learn from the 1970ies

A lot of journalists and experts tend to say that this situation is ‘unprecedented’, and they are right. A combination of war in Europe, an energy crisis, an overheated economy coming out of a pandemic and zero-interest-rate policies is quite a toxic mix.

Similar to 2022, one of the main causes of the stagflation in the 1970ies was an energy crisis. First, the 1973 oil crisis was triggered by supply shortages due to the Yom Kippur War, and then secondly the 1979 oil crisis was triggered by the Iranian revolution.

But I’m an optimist, and I think that Europe could come out of this situation even stronger than before.

Let’s look at some similarities and learnings from the 1970ies:

Similar to today, oil-producing countries used our dependence on oil as a political weapon for their gains during arm conflicts. The stock market crash from 1973 to 1974 was also happening during a time of multiple crises: the Bretton Woods system had collapsed in 1971, meaning the indirect gold standard the world was on, was over. A desperate move caused among other things by the exploding costs of an unwinnable war in Vietnam.

The Dow Jones Index dropped 46% between 1973 and 1975. And it took 10 years until it recovered. One of the learnings was that the US invested heavily in becoming less reliant on OPEC exports, an endeavor Henry Kissinger announced as “Project Independence”. This also included using domestic natural gas reserves, via the controversial process called ‘Hydraulic Fracking’. Meanwhile, Europe, and especially its economic powerhouses like Germany, chose to play stupid games to win stupid prizes and even increased their reliance on cheap Russian natural gas in the past decades. Ouch.

I’m too young to tell you how it felt to live through the energy crises of the 1970s. But movies like Mad Max, that play with the big question ‘What if we run out of oil?’ give you a glimpse of how doomy and gloomy the sentiment must have been.

The original Mad Max script was co-written by journalist James McCausland, who said the story was inspired by the 1973 oil crisis and the civilian response to the phenomenon in Miller’s native Australia. Per McCausland, civilian motorists began hoarding oil for fear of a shortage, with access to oil trumping the importance of working together and maintaining social bonds. (Source)

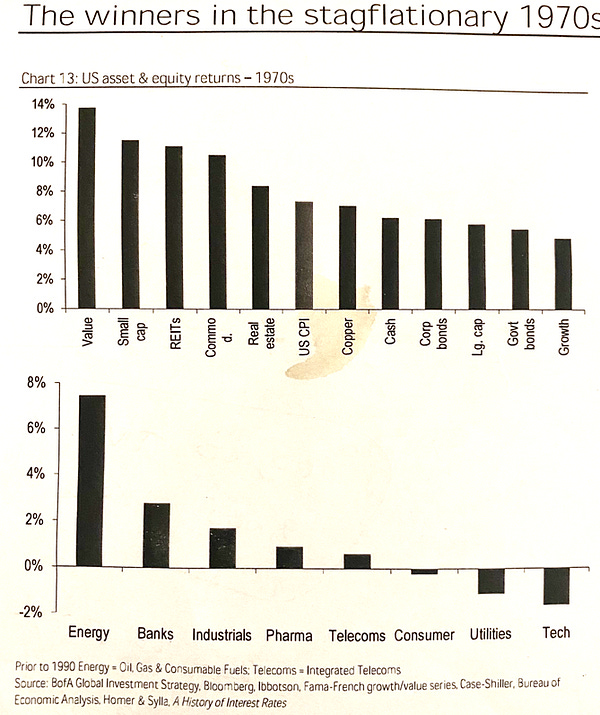

In terms of investing, the rules have changed and the good old ‘just put your money in an MSCI World ETF’ may not be the best advice anymore. I’m not giving you any investment advice here, as I’m mostly clueless myself. But risky growth stocks and just holding cash at 10% inflation seems to be a bad idea in an uncertain environment. Value stocks, gold, commodities, and of course bitcoin may be things that could be interesting in the coming years.

That’s it for now, I’m sure this topic will, unfortunately, stick with us for a while, so I think I’ll write some more stuff about it in the future.

Like what you read? Send this newsletter to a friend, subscribe (if you haven’t yet) and follow me on Twitter.

Photo by Ömer Haktan Bulut on Unsplash.

This newsletter reflects the author’s opinion and is intended for educational and entertainment purposes only. Be aware that this newsletter should not be considered investment advice in any way. Investing in Bitcoin and other assets is risky. Please be careful.